Click here for Home

GOING THE DISTANCE

"MEMOIR PART 1"

by GENGHIS

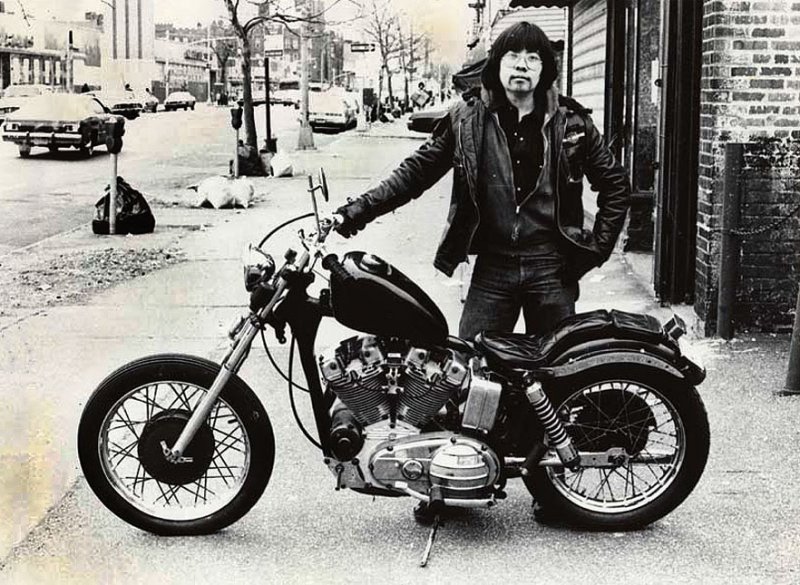

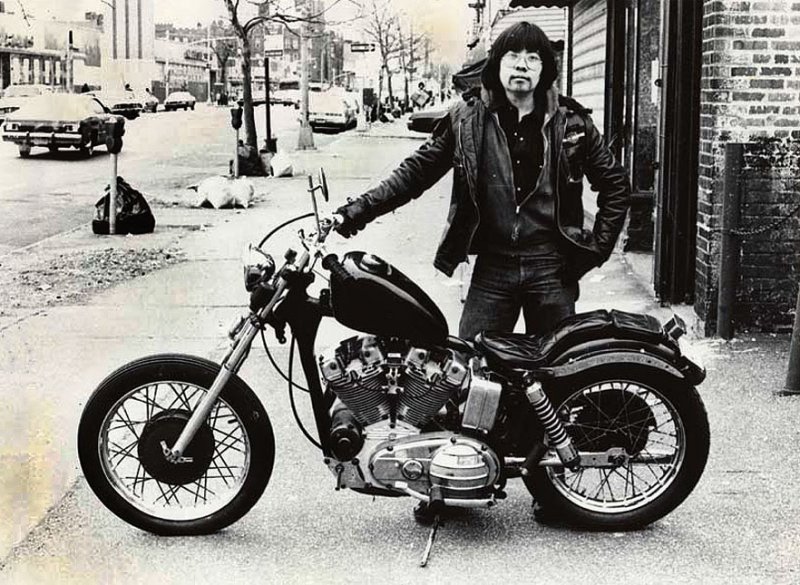

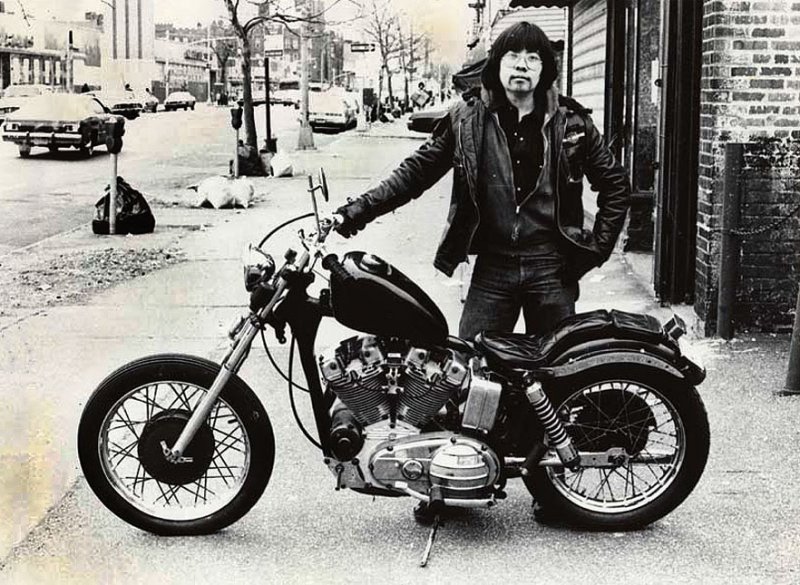

Photo by Genghis

A MILLION YEARS AGO: Genghis with "Sally The Bitch" early 1970s.

In a recent interview, Michael Connelly, who is the author of the famous Henry Bosch series of crime novels, was asked who he wrote for when sitting at the keyboard. Paraphrasing him, he said, "I write for myself. I never actually think about what readers would find interesting, I write what I find interesting. Anyone who writes for an audience doesn't come off as authentic." That's just about it. I am in total agreement, and that's my motivation when I write. I always write what I find to be interesting. Right now, my interest is in writing my memoir. This will be far and wide ranging, as wide ranging as my memory files can stretch it without breaking.

I'm not sure in the end what this will contain, for I write in the moment. I tend to write as a stream of consciousness, unsure of what will come next, or ultimately, how it will look when finished.

I can tell you one thing for sure: I'm writing what I find to be interesting.

If you don't dig it, read yer own memoir, okay?

I'm prefacing this memoir, because there's a chance that nobody will have the slightest interest in my life. Doesn't matter man, because I do. It's all about me, baby. Haven't ya learned that by now?

Part of my interest in this, is nostalgia, pure and simple. It has been said that memoirs are the product of ego. That might be true. Everybody has a life and is entitled to chronicle it. Now, whether or not anyone else is interested in putting in the time to read it, is a different story, but I hope that you will read this. If not, then hey---don't let the back arrow hit ya on the way out. You can always go back to Googling "Justin Bieber" for the sixteenth time.

The term "memoir" comes from the French, meaning reminiscence. I admit to being vulnerable to varying degrees of nostalgia, especially when it comes to my Harleys.

Nostalgia: Sentimental longing for the past, typically for a period or place with happy associations.

I'm happy with my my Harley 74, and was happy with my Sportster.

Believe it or not, I still miss my 1968 Harley XLCH, Sally The Bitch, even after I left her for my love-of-my-life-Harley, Mabel---my '71 Shovelhead. I know Sally's somewhere in England, but will probably never lay eyes on her candy apple red self, or ears on her metallic exhaust rap again. The sound of a Sportster is so different and distinctive from that of a big twin, and the magnificent sound of the Sportster still makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, even after all these years of Shovel Worship.

But what led to Sally, and then to Mabel? Here's the deal.

I was born in 1947 in Jackson Heights, in Queens, New York, to parents who both emigrated from southern China in the 1910s. That would account for my southern accent and my fondness for southern fried chicken and the pedal steel guitar.

I was the only one of four kids born in a hospital, instead of at home. I was the baby of the family. My two older sisters Dottie and Nancy and my older brother Don were born at home. Home was a three story building my parents owned, with the Chinese laundry they had on street level, our three bedroom railroad apartment on the second floor, and the third floor apartment that we rented to Mrs. Spagnuolo--a kindly old woman. Building legend had it that the tenant who preceded Mrs. Spagnuolo, committed suicide in the bathroom, and that the tenant's ghost haunted that third floor apartment. I reluctantly admit to hearing noises from the Spagnuolo house ("house" is used generically in New York for any home, whether house or apartment) when nobody was home.

I was considered the black sheep of my immediate family, and no wonder, by comparison. My brother and sisters were quite conformist compared to me, and my parents were unprepared for such a rude awakening at the very end of their child-bearing years. I wasn't quite The Omen, but prettty close by non-supernatural standards. Like a lot of future bikers, I hated authority in most any form starting at the earliest age, and resisted being told to line up and follow, like a good little boy. I fell like a possessed stone into a habit of engaging in fistfights, which perplexed my parents whenever they were called to the principal's office. I think the worst time was when I tried to throw my best friend out of a third story window in junior high school. I didn't succeed, only because my friend Paul was bigger and stronger than me--but I tried.

I've worn glasses since the age of seven, and had the unfortunate habit of breaking my glasses in fights. There was an incident in either fourth or fifth grade, when a kid I beat on, caused my glasses to fall under his feet with his flailing arms, breaking one of the lenses. Not wanting to take the blame for yet another pair of broken glasses, I finished beating the crap outta the kid, and dragged him by the scruff of his shirt the three blocks from the schoolyard to my parents' store. I presented the bodily evidence (in this case, the kid's body) of my innocence to my folks. The kid's slobbering apology saved my ass. I loved my father and feared him, because he was of an older generation that believed in the righteousness and effectiveness of corporal punishment.

Speaking of school, I always hated it. So much so, that I'm suprised that I lasted long enough to make it to college. I can remember vividly, as surely as this was the actual day that it happened, the day when my mother dragged me kicking and screaming to my first day at kindergarten. No, no, man---I did not want to go to a place where teachers would boss me around.

From that day onward, it was all downhill in my school experience. I hated school, I hated homework and I hated studying. I hated the school environment, where one was expected to think and behave in the box.

As a result, I was a very poor student who just managed to get by with passing grades.

I found school extremely stressful, and ironically for someone who hated the regimentation of school, I developed into a terrific worker with an exceptionally strong work ethic, after I was done with school. Equally ironically, I also tolerated the rigors of martial arts training where I had to totally submit to a dojo's rules and regs, and learned how essential this breakdown of a student's ego was, to further advancement in learning technique. I later imposed this basic tenet to my students when I had my own dojo. An unquestioning student is one who will learn, and learn more quickly than one who resists. The combat arts is really the only instance in my life when I voluntarily joined an organization, rare in my life because I'm a loner.

A "joiner" I am not.

The martial arts school that I joined was unusual, and fit my temperament and past history of fighting as a kid. More on this later.

Again by comparison, my brother and sisters were uniformly terrific students, that fit the asian stereotype of the classic overachiever. This deepset disdain for regimentation, in a perfect storm marriage with my tendency to be a loner, is the key to my personality This abhorrence of being around groups of people, with the attendant peer pressure to act and follow in prescribed ways, has shaped my life in the most basic of ways. I and Me-Tooism are like oil and water.

One factor that might've led me to be such a loner in life, is that my siblings were so much older than me, and growing up for me was similar to the "only child" experience. My brother and sisters were young adults during my childhood.

Don't tell me what to do, man!

I will say this about conformity in my life: I am a contradiction. In some ways, I conform quite well. With regard to work, as I mentioned, I have a tremendous work ethic. I can do the 9-5 thing in my sleep, without batting an REM pattern. I mingle with, and interact with people in the work environment extremely well. Yet, in other areas of life, I am so unusally nonconformist. I think a perfect example of this is my choice of clothing. For the past forty years, all I've worn as a baseline, are black jeans and black sleeveless pocket t-shirts. Of course, I will wear layers of flannel shirts and thermal clothes in addition to the "baseline" as dictated by the weather. But the black dungarees and t-shirts remain. People who see me probably assume that I never change my clothes, but what they don't know is that I just happen to have lots of black jeans and black sleeveless t-shirts in store, but no other color of baseline clothes. I admit to knowing no one else who has worn the same type of clothes every day for the past four decades, with total disregard for variety and color.

As a biker, I believe that I am seriously non-conformist. I ride alone, and I sure don't socialize with other bikers in real life. Interaction on the internet doesn't count. There's too much distance between keyboards to be considered socializing. With respect to biker trends and bike style trends, I'm definitely nonconformist. I know what I like, and I know what I think is peer pressure-driven garbage--and I will say so, which may just be the underlying basis for my biker subculture writing. More on motorcycles later.

"Plastic Fantastic Lover" was a song by the Jefferson Airplane in the '60s, about the prevalent influence that TV had on society by that point in time. So it was with me, while watching episodes of Route 66 on my little black and white television. These stories about these two guys riding around in a hot Corvette, caused me to fall in love with Vettes, a love that led me to buy a used '64 Vette at the age of 19. My passion for cars then was overwhelming. Cars and car racing filled my entire life with passion.

This love of cars survives to this day, despite its twin obession, the love of motorcycles. One passion never crowded out the other.

That '64 Vette was a hot car, man. 327 cubic inch 365 horse motor with a four speed, with exhaust dumpers that made it twice as loud as any Harley with straight pipes, that was the beginning of my motorvatin' life.

A radar detected 110 mile per hour, early-morning scamper on a deserted Triboro Bridge, gave me one of a trio of speeding tickets that led to the revocation of my drivers' license. I came to the end of the all but empty bridge on the Manhattan side with pipes blasting like the third world war, to find a cop car parked broadside in the midde lane to form a roadblock. The radar gun, done done me in, man.

Hot rod culture was alive and well in Queens, which was a mere couple of miles (it might as well have been a thousand miles) from The City (Manhattan) where no such abnormal fixations plagued the citizens. Citizens of The Big City didn't even like cars, never mind hold a passion for 'em.

Places like Jackson Heights were more like small towns in the south in the 1950s, except that they were technically a part of New York City in name. Attitudes were seriously small town, in spite of the close proximity to The Big City.

In Jackson Heights alone, there were at least four speed shops that existed concurrently.

I had an unfortunate experience with one of the speed shops, where I bought Mickey Thompson mag wheels (which were actually made of aluminum) for my Vette. With the red line tires I put on 'em they looked killer, man. The only problem was, the day after putting these on the Vette, I found all four tires had gone flat. It seems that these early mag wheels were too porous to use with tubeless tires, so I had to had tubes installed. I loved the look of these wheels too much (I should've gone with steel Cragar S/S mag wheels--but, noooo, I had to have alloy wheels)) to return 'em, so I lived with the tubes.

My Motorvatin' Life took a turn in 1968, when the draw of Harley-Davidsons became too much to bear. It was like a constant brain itch that couldn't be scratched, because my skull kept getting in the way. As much as I loved my Corvette Sting Ray and cars, I knew I was destined for Harleydom. It had to be a Harley. I knew other young guys in Jackson Heights that were more interested in Britbikes, but not me. The influence of older bikers who rode Harleys I knew and grew up with as if they were older brothers, swept me to the Harley Side. The only question was, which Harley would make that itch go away? My tastes in Harleys then was much different than it is today.

In the late 1960s, Sportsters were perceived differently than they are now. Instead of as a stepping-stone to a big twin, or as an entry-level Harley as they are depicted now, they were seen as an end to itself. In the mid to late '60s, the Sportster XLCH was seen as the King Of The Street, and was treated as such by the motorcycle magazines of the day. Back then, the XLCH had publicized brass balls, too big for any jockstrap to hold as it made its way down the quarter mile to victory lane. The Killer CH blew the doors off of cars, and the skirts off of Beezers and Trumpets. Look out, man!

Let the Limeys have their Lightnings that they gazed at whilst they sipped tea at the Ace Cafe, this was All American Muscle, the mighty XLCH!

By comparison, motorcycle magazines treated the big twin as a tired old geezer, just waiting in the rocking chair for retirement---or a Shriners Club with a parade first gear. No man, it had to be an XLCH for me. I wanted the most badass, and the XLCH was Her Badness Incarnate.

Here was the problem: I was just a college kid with a car, and no money. How would I get the bread for the bike? There was only one way, and this led me to a tough decision: Keep the Vette or sell her for the money for the Harley. It was The Harley, baby! There was no real choice considering the brain itch for a bike that I was afflicted with. I just had to scratch that itch, and the only way to have a satisfying scratch, was to walk into a dealership and plop the cash down for My Bike. It would take roughly two grand for the bike. This doesn't seem like a lot now, but for a 1968 college kid, it was a mint. Back the Vette went to the used car lot on Queens Boulevard that I bought her from, and onward to Harley-Davidson of Manhattan for My Destiny.

As the Duck Commander would say, the situation causing me to sacrifice my '64 Vette for money to buy the Harley came to a happy, happy, happy ending, when I later replaced her with my current 1971 Corvette Stingray (early Sting Rays used two words, "Sting" and "Ray" while later "Stingrays" used one word, conjoining the two words) who I named "Mary." I love Mary even more than I loved the '64, and this Vette's not gettin' away from me. Nope. Not again! She's here to stay. Acquiring Mary assuaged some of the regret at losing my '64 Vette, and believe me, there was plenty of seller's remorse about losing the '64.

Motorcycles are all about emotion.

Everything about motorcycles is about emotion, from the way it feels to ride 'em, to the way they look, to the way they smell, and yes, to the way you look when riding them (can't ignore the cool factor, especially if you're a young guy like I was when I got my first Harley), it's all about emotion, man. From a purist's point of view, forget about clubs, forget about the Sturgises of the world, forget about impressing the friends from around the corner. It is all about an emotional response to The Bike. Even the way one would look when bookin' down the highway at 70 on a loud Harley, is an emotional experience, if there was nobody else there to witness it except the rider himself. He is aware of the figure that he and his bike are cuttin'. He knows. Does a beautiful thing happen on the blacktop if nobody sees or hears it? Does a tree fall in the forest if nobody is there to see it?

The emotional buildup to getting my first Harley-Davidson on the streets, was incredible. I'd already left the meager deposit on my brand new 1968 Harley-Davidson Sportster XLCH. She was H-D orange and black, with a Bates solo seat and pillion pad. Gleaming Evil Orange & Black, man, she was a feisty angel waiting to stretch her legs on the highway. When I finally picked her up, I thought my heart palpitations were clearly audible on the showroom floor at Harley of Manhattan. Harley-Davidson of Manhattan was a storefront dealership, on 76th Street between First and Second Avenues. It was long and narrow, being only about twenty-five feet wide, but extending back like a railroad apartment. The service department took up the back portion of the dealership, and dual swinging doors separated the showroom from the shop in the back. Both departments were about the same size, it was a 50/50 proposition. I cannot find the words to describe the way it felt to ride My Bike over the 59th Street Bridge to Queens. Let's just say that it was an emotional experience and leave it at that.

The year after I acquired My Bike, I met my first wife Nancie. In fact, it was because of my bike that I met her. I was parked on Second Avenue and St. Marks Place in front of Gem Spa (our Ace Cafe) with some other bikers who had their Harleys parked. The row of gleaming motorcycles stretched a third of the way down the block. Nancie came up to me, and I knew that she wanted me to ask her if she wanted to go for a ride, so I did. And she did. That was the beginning of our relationship, which turned out to be a turbulent roller coaster.

Nancie and I were together for four years. Nancie believed she was infertile, because before she met me, she never used birth control and never got pregnant. But guess what? She became pregnant at the end of 1969.

I worked as a medical photographer during this period, for a medical facility called the Pack Medical Foundation, which was located on 36th Street between Madison and Park Avenues. My job was to document surgical patients before and after plastic surgeries. These surgeries ranged from the cosmetic, to the truly serious---cancer patients.

The most intriguing cases for me, were women who were slated to undergo breast implants and breast reductions. My clinical interest here was definitely heightened.

We were elated that Nancie was expecting, and in 1970, our son Michael was born. I thought to myself, "Another biker is born into the world!" Mike was a little bundle of joy, with head full of hair and inquisitive eyes and a quiet demeanor. I guess I felt what every father feels when a first child of his is born: "I feel like a man now, because I've fulfilled my masculine, primal duty--which is to procreate." At least, I felt that instinctively, though I didn't vocalize this.

After working at the Pack Medical Foundation for a year, Pack went bankrupt, and I found myself unemployed. This was not a healthy situation for a young guy with a wife and son to support. During the summer of 1968, I worked as a motorcycle messenger for the Quick Trip Messenger Service in Manhattan. My job then was to deliver things in NYC and out of town. I was essentially on my Sportster "Sally The Bitch" for 8 hours a day, five days a week. Sure, it's fun to ride, but can be grueling on that type of schedule, sometimes in crawling city traffic. After I lost my job as a medical photographer at Pack, I went back to my job with Quick Trip.

Quick Trip was run by an ex-cop named George Shaw. He always called me "The Indian" because of my long hair that I kept tied with a bandana. George was a fair but tough boss, who I liked quite a bit, and I kept in touch with him for years after until his death. After I got into medicine full-time, I gave George medical advice and guidance about his diabetes from time to time. One day when I called the Quick Trip offices, I learned he was gone. I was informed that he finally succumbed to the ravages of his diabetes.

Returning to Quick Trip was a come-down, primarily because of the reduced wages I received, compared to the medical photography job's take-home pay. Messengers work on a commission, and I was lucky if I took home ninety bucks a week. However, it sure beat being unemployed.

Messengers get treated like crap. Secretaries call you "boy," even if you are several years older than they are. I gradually moved on to delivering with a truck instead of my bike, which I was happy about. I was tired of exposing Sally to the kind of abuse that hard city riding all day long imposed on motorcycles.

One time I was making a delivery with an older messenger I was working with.

This was a 59 year old black man named Jim.

A twenty-something year old secretary where we delivered, called Jim, "boy."

I lit into her and reduced this airheaded secretary into a pile of slobbering mush, by the time I was done with her. Jim and I left with her in tears, wanting her mommy and her Barbie Doll. There was another time when I delivered a piece of artwork to a museum. This art was made of lucite, and I dropped it in the loading dock and it broke into several pieces of art. Oops. I later learned that this piece was valued at $20,000. Fortunately, Quick Trip was insured against damage and loss!

There were a number of bikers working for Quick Trip, and among them was a Pagan who rode a straight-leg rigid pan. This was a guy who I witnessed running for his life in the East Village from some Hell's Angels, who eventually had to leave New York City because he was so sought-after, and I don't mean by employers. His nickname was "Patch" because he wore an eye patch. The war between the Angels and Pagans in New York, was hot and heavy then. Patch wasn't exactly the friendliest guy in the world. Armed with a scowl and his pirate patch, he cut an unsympathetic figure. I assume that he had one eye enucleated, necessitating the eye patch. The last time I saw Patch, he was hiding in a vestibule of a brownstone on St. Marks Place, his hair drenched with sweat from running. I never saw him again.

There was another biker who worked at the service named Mark, who gave me my first ride on a Harley 45 trike, which ended with a slow-speed crash into some garbage cans. This little trike joyride took place in a cavernous courtyard in Queens. Queens is unique, in that it houses some of the most ornate art deco apartment complexes, with large fields of courtyards at their center. I don't recall ever seeing any architecture like this in Manhattan.

Regarding my unsuccessful ride on the trike, hey man, I was instinctively trying to lean the three wheeler to make 'er turn, but it doesn't work that way! They oughta put steering wheels on those infernal things. If it ain't two wheels, then it oughta be four. In order for her to be mean, she's got to lean! The last time I saw Mark, he was laid up in the hospital with numerous injuries, due to a high speed wreck on the FDR Drive. He crested a blind grade at 80 miles per hour, and when he landed on the other side of the hill, he rode right into the back of a car. This was on his bike, not the three-wheeler.

I met the only New York Hell's Angel that I personally knew in front of Quick Trip when the Quick Trip office was on East 25th Street (it later moved to Tenth Avenue). His name was Mario. Mario at that time, was a New York Alien. This was before the NYC Aliens became the New York City chapter of the HAMC. I found Mario standing near Sally, eyeing her. He was wearing his Aliens MC colors.

I said something like, "What's up?" Mario said with a glint in his eye, "I was thinking of stealing yer bike." I was never sure if he was kidding or not. He was also a Sportster enthusiast, riding a wrinkle-black Sporty with an add-on hardtail. He told me that he would never abuse his bike by using it for messenger service work. It became apparent that messenger work wasn't going to adequately support us. I thought that a fresh start on the west coast might be appropriate, which dovetailed with my long-held plans to move to California. I would find medical photography work, where I had dreamt of living.

At this point, my plans to move to California solidified. It was my dream to move there and ride there, something many bikers considered their primary motive for the move: Hands lazily guiding the handelbars, bike gently weaving from side to side, almost rocking the rider, hair (no helmets in California!) swept back by the caress of the warm Californian air, heaven, heaven.

The draw of the proverbial Land of Milk and Honey, can be irresistible to bikers. The sun, the highways, this was the state that was the veritable cradle of outlaw biker culture. How could I resist? So I didn't. My in-laws were already settled in San Diego, so Dago was the target landing site. Presumably, Nancie's folks would help us in finding a place to live.

Moving to California was something I had planned before I met Nancie, and I was determined to follow-through with the plan.

I bought a used Ford Econoline van for six bills, shoved all our belongings in there, including my XLCH Sally The Bitch, and off we (my ex, my son Mike and I) went cross-country. We made it to San Diego in one piece, with a few minor glitches along the way. A cop stopped us on the interstate in Ohio and gave us a hard time. Another cop stopped us in Flagstaff, Arizona and gave us an even harder time, theatening to force us to empty out the van in a search or drugs (there were none). He eventually decided to stop wasting our time and his time, and let us go. When we passed through the panhandle of Texas, some of the locals gave me a hard time about being a "long-haired hippie" before they tired of their game. Just little stuff, but aggravating stuff, to be sure.

True to my in-laws' word, they did find us a place to live. It was a little beach cottage a few yards from the ocean, on Mission Boulevard in Pacific Beach in San Diego. I called this little house The Alligator because it had a roof covered with green shingles. They resembled reptilian scales. There was a smattering of surfboard shops in the neighborhood, frequented by blonde people. Everybody there seemed to be preponderantly blonde. I swear, I thought I landed in Sweden, or in a rendition of the "Stepford Citizens."

One of my new neighbors was a friendly woman (who was blonde, natch), who said to me in awe and all sincerity, "Hey, I've never seen a Chinese person before." I tried to decide whether she was puttin' me on, but her complete lack of guile decided me otherwise.

Apparently, there were few or no asians in San Diego then.

Interestingly, when I met my wife Patty in 1982, she too, said to me, "You're the first Chinese person I've ever met." More on this later.

"The Alligator" was also close to Balboa Park. I loved The Alligator, and I loved mostly everything about San Diego. The weather was perfect, with cool temps at night in the summer, so that air conditioning wasn't necessary, and temps in the winter never below 60.

I learned a painful lesson about San Diegan architecture, when the nights became very cool there. The heaters in The Alligator, like most houses in Pacific Beach, consisted of grated units on the floor. This was quite different than in New York, where the heaters are stand-alone radiatiors. On more than one cool occasion, I stepped on hot grated heaters in The Alligator while stumbling around in the middle of the night.

The San Diego area is just picturesquely beautiful, with scenery that any biker would dig riding in and through. The roads were gorgeous. The place was everything I pictured in my mind in New York, when I dreamed of riding my Harley in the warm California air.

I loved living adjacent to the ocean. San Diego did have some problems for me, though. One minor problem was that parts of my bike that were not painted or chromed, rusted at an alarming rate. For example, the fork tubes. I'd removed the tubes' rubber boots in New York, and never bothered to have the exposed tubes chromed. In NYC, the tubes never rusted.

I'd never seen anything like this. I didn't realize how quickly corrosive the sea's salt air was.

A distinctive feature of San Diego, were the purple lawns that were popular in the early '70s. I was told that this color resulted from a species of small purple flowers that San Diegans planted on their lawns. According to a San Diegan who I talked to who recently moved to NYC, this is no longer the case. In fact, she had no idea what I was talking about. This purple flower must've gone the way of the dodo bird in San Diego since I lived there. Lawns must conventionally green there now. How boring is that?

Another problem was the small matter of employment. I spent the better part of a month looking for a job as a medical photographer, to no avail. There were none to be found in the immediate area. I resorted to looking for work outside San Diego.

I ranged as far as Los Angeles and San Francisco, and my reconnaissance trips there failed to come up with any opportunities as a medical photographer.

Medical photographers were not in demand in California at that time.

On one of my trips up the coast, I stopped to see an old friend, Spade George. Spade George was an ex-pat New Yorker, who belonged to an NYC outlaw club called the Rat Pack M.C. George emigrated to California a couple of years before. When I visited Spade George in Daly City, he seemed as deranged as ever. Some hardcores never change, man. George currently has a shop, and if ya Google "Spade George," you get links to his motorcycle shop. When I left George's house in Daly City, he was out there shooting a .38 revolver in the air. Just another quiet night with Spade George.

My employment situation in San Diego was in critical condition . The money that I had, was on life support.

A Do Not Resuscitate sign wasn't necessary for our bank account, because there was nothing to resuscitate.

In my desperation, I interviewed for a mortician's assistant job (no good, Nancie said she wouldn't touch me if I took that job.) I looked for freelance construction jobs (no good, I was told only union members could work construction). I answered a newspaper ad for salesmen jobs by going to a seedy motel room where interviews were being held. I knocked on the door, and the guy that opened the door, looked at my feet and said, "You can't be a salesman in those!" He pointed down to the two dollar sneakers I bought that week at a five and ten---my boots had finally fallen into disrepair and I had to trashcan 'em. I didn't even make it past the door of that motel room.

I finally caught a break when my brother-in-law Mickey referred me to an automotive shop he used to work for. This was a chain of two independent Volkswagen repair shops, owned by a guy named Dan. Dan (who was blonde, wouldn't ya know it?) hired me to move volkswagen engines in my own van from shop to shop as needed. One shop was in San Diego and the other was in National City a few miles away. The freeway that I took between the shops took me past Jack Murphy Stadium (now known as Qualcomm Stadium) where the San Diego Chargers played.

This was backbreaking work, as I had to move the engines in and out of my van, but hey---it was a job. It was a job that paid off the books, however, that only paid about sixty bucks a week.

One week into my employment, Dan pulled me aside and pulled out a stainless .45 ACP Colt pistol and said to me, "Do you know who yer brother-in-law is? He's the guy whose father reported me to the IRS fer paying guys off the books!" I told Dan that I had no idea that had transpired. I told Dan that he could trust me not to make any noises about him paying me off the books.

Dan believed me, and didn't fire me. He did have one last admonition for me though. He said, "If I ever catch you stealing parts from me, that'll be it." I reassured Dan, that that would never happen.

After that, I went to my father-in-law Herb and let him have it for not warning me about his snitching to the IRS about Dan, before I applied for a job with him.

I grew to really like Dan during my employment in his shops. He was a cool guy.

One day while I was driving my van on a San Diego street , four cop cars converged on me and pulled me to a stop. Cops came out with guns drawn and ordered me out, and onto the ground. I complied. After searching my van, they let me up and gave me an explanation for what just happened. One cop said, "Sorry, this was a mistake. There's been an asian guy with a white van (my Econoline was white) with New York plates, who's been burglarizing houses in this area." The coincidence was unbelievable. An asian male? In a white van? With New York plates? Ooookay. I perhaps naively asked them if they could give me an official note stating that I wasn't that guy, but they declined.

After this little incident, I had a brilliant idea.

I painted the name of Dan's shops on the sides of my van, to distinguish my van from The Guilty Van. There ya go!

Unfortunately, this free advertising for Dan's business on the sides of my van, did not go over big with Dan. He persuaded me (this time, without the use of his Colt pistol as a prop---Dan was softening up to me) to remove the business' name from my van. There was a mechanic who worked at the San Diego shop named Frank (who was blonde, by the way) who owned a Honda 125. Before I decided to move back to New York, I arranged for a driving test at the DMV, to qualify for change to a California drivers' license. I'd already taken the four-wheel part of the test with my van and passed. On the appointed day for my motorcycle test, it was just more convenient to take Frank's little Honda to the test site. I was already at the shop where Frank's Honda was. It was easier to take the Honda than go back home and ride the Sportster for the test. Since Frank offered, I accepted!

The test site was a few miles away. I learned how dangerous these little bikes were on the way there. With California drivers whizzing by me on the freeway at 80 miles an hour, and me on this little piece of crap barely getting to 45 (if that), I felt like a sitting duck.

I might've been one of Jase Robertson's test subjects for a Duck Commander Triple Threat.

That wouldn't have been a worry if it was Uncle Si in the duck blind.

I managed to get to the testing site in one piece, wishing like hell that I'd gone home to get Sally The Bitch.

Of course, I passed the test.

The ride back to the shop was just as harrowing.

I shouldn't have bothered. Shortly after passing my motorcycle test, we decided to do the sane thing and move back to good 'ole New York City. This $60 a week was ridiculous. Even the $90 a week working for the Quick Trip Messenger Service in New York was better than this. Before we departed for New York, I thanked Dan for giving me work. Dan said to me, "Hey, you're allright. I never (here we go again) had a Chinaman workin' for me before."

All bad things must come to an end. So it was with our short-lived residence in the great state of California. The plan this time around, was for Nancie and little Mike to fly back. I would drive back to New York, under separate cover. Unbelievably, I made the trip back to The City in three days. I achieved this by driving non-stop every day for countless hours. I didn't stop to eat. Instead, I made sandwiches with these little cans of tuna and meat spread while I drove, and ate while I drove. The drive home took on an entirely different feel than our drive to San Diego. The trip to California was a casual, 10 day tourist trip with stops in places like Santa Fe, while the drive back home felt like a mission to be accomplished, to overcome the obstacles of distance and time. Like a homing pigeon with a delivery to accomplish, only the destination reached at max speed, mattered.

Home.

The word means little to some, much to me. If I have to explain, then ya wouldn't understand.

I entered the metropolitan area via the New Jersey Turnpike. One of the most significant memories that has continued to float up like a gorgeous mosaic in my mind over the years, was the sight of the skyline of New York City as I approached her from New Jersey.

If it's possible to realize in a flash what the score is late in a game, this was it.

The score in this case, was the homesickness I didn't realize I was suffering, until New York City came into my view.

Inexplicably, I didn't feel homesick for New York during the period I lived in San Diego, but it all came to me in a rush like the peak of an acid trip on seeing good 'ole New York, man. It was at that moment when I realized how much I loved NYC. It was like an inner thought that was hiding in the back of my mind, making itself known with a passionate debut at the front of my mind. Once it hit the landing pad of my frontal lobes, I knew that I was home.

Life resumed for us after our return to New York. I went back to work at the Quick Trip Messenger Service, and my marriage slowly eroded beneath the surface. This period after we returned to New York was significant in a bittersweet way. Bitter because the marriage was heading for the exit ramp at medium speed in the right lane, and sweet because my daughter would be born among the ruins of the marital union. It was sweet also, because I took a change of direction in my work life, which improved dramatically during this period. While the marital union was eroding, my Father Life and my work life, was being reconstructed.

Heavily weighing on my mind, was the fact that the lowly salary from being a messenger was inadequate to support a forthcoming two-child family. Nancie became pregnant again. One advantage of working for Quick Trip was that I could plan my delivery trips around clandestine job-seeking interviews. I was determined to move upward in scope in my professional life. The area I concentrated on, was photography. I'd already made the first step when I worked for the Pack Medical Foundation before it went bankrupt, and it was now time to take at least a sideways step back into photography, before I could get a medical photography job (which was harder to find) again.

Ultimately, I wanted to end up in ophthalmic photography (eye photography in medicine). In order to do that at this juncture of my life, I realized that I would have to seek a more tangential photography job until an ophthalmic photography opportunity became available. My brother Don was an established ophthalmic photographer, and he would be on the lookout for one of these rare eye photography gigs.

One job interview took place between messenger deliveries at a commercial photo lab called Edstan Studios. The bosses were Ed and Stan, and they hired me to work as a black and white print processor, a skill that I was well versed in. This was a skill my brother taught me when I was a teen, and had utilized professionally at the Pack Medical Foundation. This was not only a good stopgap move back into photography, the job also gave my growing family greater security, because of the increase in take home pay. This job became a bridge to my next medical photography job.

A job in ophthalmic photography became available during my time at Edstan Studios, and this was the position as ophthalmic photographer at the Beth Israel Medical Center on 16th Street and First Avenue in Manhattan. I got the job, but was surprised at what my office looked like when I entered it. It was a converted mens room, replete with the plumbing fixtures for the urinals still attached to the wall, although the urinals were removed. I expected to smell urinal cakes during my inspection of this room. The places where the toilets once sat, were clearly demarcated by the impressions they left in the stalls. The diamond patterned floor tiles around where the toilets sat were grayish, while the areas below where the toilet bowls sat, were still a pristine white. The holes where the toilets drained, were still there, unplugged and uncovered. If this bathroom was more complete, I wouldn't have had to leave my office to relieve myself.

One advantage of working at Beth Israel was, I was able to work on my bike while I worked there. At the time, I was in the process of molding Sally The Bitch's frame with fiberglass. I had disassembled the Sportster, and after having the frame sandblasted at Hygrade Plating in Long Island City, I took the frame to the hospital to work on. I filed down the frame's protuberances prior to molding in the ERG Room (electroretinography, which measures electrical responses of retinal cells) in the Department of Ophthalmology. Whenever I had some free time, I'd sneak in there and do some more work on Sally's frame.

Once I finished filing down Sally's frame, I took it back to my apartment at 233 East 3rd Street, to finish the molding job. As for materials, I bought a quantity of fiberglass resin and fibers, at a store on Canal Street in Manhattan. I was careful to protect my skin from stray fibers (once those got into your skin, forget it!) by wearing long sleeve shirts and surgical gloves. I also wore goggles and a surgical cap over my hair. Molding with fiberglass was far superior and durable than bondo. It became one with the bike, never to flake off.

After molding the frame, I took it to the basement of my parents' store where I painted it candy apple red lacquer. I bought spray cans of Kalifornia Kustom paint from the local auto parts store. I hung the frame with baling wire from a water pipe along the basement's ceiling, and hosed down the basement floor prior to painting, to minimize dust in the air. I used one silver base coat, ten cans of candy apple red and two cans of clear, with wet sanding between coats to smooth out the runs. The end result, was perfect. I surprised even myself with how professional the paint job looked. I then reassembled Sally upstairs in the middle of the Chinese laundry, where there was an alcove.

In early 1973, I moved to a better job at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in upper Manhattan. This was shortly before the birth of my lovely little daughter, Tiffanie. Our plan was for Nancie to give birth at New York Hospital, but the best laid plans of mice and men and parents, was diverted by a shorter than anticipated labor. End result? I ended up delivering Tiffanie at home. Although as equally as photogenic as my son (are parents always biased this way?) was, Tiff's personality was diametrically opposite Mike's. While Mike was quiet as an infant, Tiff seemed to cry 24/7. Colic? Who knows. Only the Shadow knows.

The bitter of the bittersweet happened, when Nancie and I split up not too long after Tiff's birth. Man, wotta way to spoil a blessed event! However, the end was not just near, it was there for my ex and me. Nancie and I got divorced the following year using a divorce kit we saw advertised for $110, in the back of the Village Voice. Nancie and I had joint custody of the kids, where The Ex had them during the week, and I had 'em during the weekends. Life goes on, baby.

Another pivotal point ocurred in my life, in 1976. I became interested in studying the martial arts. My motivation wasn't exactly self-defense, as I'd spent much of my childhood fighting. Fistfighting was just part of growing up in Queens in my crowd. In Jackson Heights, there was a clear demarcation ethnically, and these ethnic boundaries dictated where you stood on the aggression/domination ladder, and whether you beat or got beaten.

There were the in-betweens, who were numerically insignificant, like hispanics and asians. There was no interaction with African-Americans, because there were no African-Americans.

In the Jackson Heights I came up in, There was not a single African-American. African-Americans lived in a neighboring area called Corona. Jackson Heights and Corona were contiguous, and the dividing line was 94th Street. I don't want to make too much of this (but it is significant as to era and place), but we called 94th Street the Mason-Dixon Line. People living east of 94th Street were black, and those living west of this imaginary border, were white, with a few asians and hispanics.

94th Street was like the dividing line that bisected Frank Gorshin's face in that Star Trek episode where half of his face was white, the other half being black.

There might've been three hispanic families in Jackson Heights that I can recall. There were exactly three Chinese families, who I was aware of. I can state this unequivocally, because mine was one of 'em, and my friend Willie's was the another. Willie was this humongous kid who weighed 230 as a teen, and built like professional wrestler. Both Willie and I hung with the Italians. In my case, my best friends were all Italian, except for Willie. This association put me squarely in the hoods' corner, both figuratively and in reality.

I already knew how to hit people.

What I wanted to do in studying the martial arts, was learn how to hit better. It was as simple as that.

As I would learn from the teacher I chose to study under, my history of gettin' into fights as a kid, made me what he called a "natural fighter."

Fighting is ultimately about intent, and the will to follow-through with intent. One can have the greatest technique in the world, but if there is a hesitation to use it to bludgeon and injure, then technique means next to nothing.

I looked around Manhattan for a suitable school. Most I discovered, did not have realistic practices, meaning that they did not actually hit each other when they practiced. The type of sparring these schools engaged in, was patterned after the sparring matches seen in karate tournaments which consisted of points awarded for getting in cleanly to an opponent's body, but stopping short of making any meaningful contact.

"How can this be any good?" I thought. It made zero sense to me. Here I was, used to hitting in fights since kindergarten, and these people won't even do that? I couldn't wrap my head around this. The people in these schools seemed delusional at best, and cowardly at worst. One day in 1976 I entered a school called the Asian Martial Arts Studio in the Soho section of lower Manhattan. An assistant instructor led me though a narrow passageway at the front, to a cavernous training floor at the back. I observed a class from a seating area just off the "floor" where I was allowed to keep my boots on. Anyone going onto the "floor" had to go on barefooted, and had to be first approved as a student before bowing onto the floor.

I was fortunate that I got there in time see some sparring practice. Two men in uniforms including colored belts, bowed to each other, before squaring off. They then raised their hands in guard positions, just as boxers would in the ring. I noted that neither wore gloves of any padding on their feet. They started feeling each other out with feints, when one of the men broke into the other's space and first planted a full-power punch into the chest of his opponent with a right hand, immediately followed by a left hook to the ribs that landed with an audible whump! The man who got hit winced and covered up. The instructor controlling the match stopped them. Apparently the man hit suffered a rib injury. The instructor asked him if he could continue. The man nodded, Yes. They resumed. Then the other man, sensing an injury, repeated his attack on the hurt man's ribs. Eventually, the man could not continue, and it was only then that their sparring was stopped.

To me, this made sense. Perfect sense. Hit and hurt, man---that's what you're supposed to do in a fight. The assistant instructor sitting with me explained that they allowed full-contact, full power punches and kicks to all targets above the waist and below the neck. Legs and head were out. He explained that they sparred without gloves to toughen up and learn how to take a hit as well as learn how not to hold back hits, and how this was essential to correct training. Hearing this, I signed up right there and then in this school.

The teacher and owner of this dojo was Richard Chin, and he became my Sifu for the next 6 years. He taught two styles of martial arts at his school, and both systems were run with the same philosophy of full-power practice and sparring. One style was Jow Ga kung fu and the other was Kuen Do Ryu karate, which is an Okinawan system.

The differences in the two styles (besides uniforms) were the "forms" traditional to each system. Otherwise, the training methods were identical. Both used a similar belt ranking system.

In the coming years, I devoted myself single-mindedly to advancing. I began training at the relatively older age of 27. By 1978, I was training at the dojo five nights a week. It took me four years of this grueling schedule to make entry-level black belt. In our systems, black belt meant something, because the training was so grueling. During my training, I'd suffered broken ribs, a broken jaw, a fractured wrist, a broken foot and lesser musculoskeletal injuries too numerous, frequent and routine to mention or even remember. The latter category consisted of sprains, ligament damage, etc. Just your normal, run-of-the-mill injuries, to be expected and dealt with without complaint or quitting.

There was an emphasis in our school, on being tough, mentally and physically.

My teacher often voiced this philosophy regarding the potential of a new student: "We'll beat the shit out of him and if he stays, then he has a chance of being good."

Black and blue was the universal color under the uniform in our school, regardless of which uniform one wore.

By 1982, I advanced in rank and ran classes at one of our two locations. We had to move from the Soho location by then, and I established a school using a rented floor at the Third Street Music School (which was actually on 11th Street). I taught both Jow Ga kung fu and Kuen Do Ryu karate there. Another of our black belts named Mike Willner, ran classes at an uptown location. One day, Mike said to me, "I'm sending a gutsy little chick to you to enroll. She's tough, I think she'll be a good student." The woman Mike was talking about, was Patricia Anne Cicchinelli, who you know as my wife Patty. Patty indeed, turned out to be a tough and resilient student.

While with Richard Chin, I began submitting articles about him and our school to martial arts magazines. From these submissions, my role in these magazines grew to monthly columns and feature articles. These magazines included Karate-Kung Fu Illustrated, Black Belt, Martial Arts Training and Kung Fu. Anyone familiar with my writing knows that I advocated realistic, full-contact, full-power hitting training, which is the way we trained at the Asian Martial Arts Studio. The majority of martial arts schools, who did not train this way, did not like being called out by me in magazines as ineffective and cowardly. I received death threats and people would threaten to come to my school and administer some kind of justice. Hey, nobody ever showed up.

In 1984 I branched off by opening my own shool on East Broadway in the Lower East Side.

While I had my school there, I continued to receive threats from others who did not like their schools being called weak and unrealistic in my martial arts magazine columns. In response, I made sure that the address of my dojo was published in my columns. Again, no one ever showed up to mount a challenge.

In 1993, I decided to retire from teaching.

During this period, Patty and I got married. When I first met Patty, she said to me, "You're the first Chinese I've ever met. There were none where I grew up." Patty grew up in Florida. Patty is half Italian and half Irish. Her Italian half is inherited from her father, Orazio Cicchinelli ("Chick" to everybody), and the Irish half from her mom, Joyce. It is interesting that when Chick and Joyce got married in 1951, their respective families were opposed to the union. Chick's family wanted him to marry a nice Italian girl, and Joyce's folks did not want her marrying an Italian. Can you imagine how Chick's and Joyce's folks , would have reacted to me? Ha!

Patty brought me to meet Chick in 1982. Let me describe Chick for you. Chick is a boisterous guy, with a coarse and booming voice. When I met Chick, he said, "So, what are ya, Hawaiian or what?"

That's Chick in a nutshell.

We've all laughed about this over the years. I never tire of tellin' this story.

The truth is, I got along great with Patty's folks. Chick's a biker, did you expect any less? Unfortunately, Chick's Parkinson's symptoms forced him to sell his Harley FLT a few years ago. The shaking of his hands no longer allowed him to grip the clutch and brake levers well enough. For a while, Chick had my old girl, Sally The Bitch, before he sold her to a Los Angeles shop. This shop then sold my old XLCH to a biker in England. Chick does miss riding, although he can still drive his car.

In the early '80s, Patty and I attended a hot rod and motorcycle show at the old New York Coliseum (yes, that New York Coliseum where the New York Aliens M.C. got into a floor-clearing fight with the Pagans M.C., which got the club absorbed in the HAMC as the New York Chapter). I'd been wishing for a shovelhead for a few years now, but kept these feelings underneath, unspoken and unacted-on. My motivation never jelled to the point where I overcame my inertia. At the Coliseum show, H-D had an exhibit with a silver Harley Low Rider displayed. I sat on the Low Rider with my feet extended to the forward pegs, hands on the bars. I rocked the bike from side to side under me, and glanced down at those massive shovel rocker boxes, and I knew. I knew I had to have a shovelhead. I loved my Sportster, but.....

I actively began saving money wherever I could, and scoping out ads for used shovelheads. In 1985, I had some money to burn.

I spotted an ad in the Buy Lines (now defunct). It advertised a 1971 Super Glide in excellent condition, a "must see" specimen. The price was four grand.

I called and spoke to the owner John Bays, who lived in Canarsie, Brooklyn. I told him that I'd be able to come see the bike on saturday.

He said he had another buyer coming to see the bike on friday, and he couldn't guarantee that it wouldn't be sold by the time I got there on saturday.

I felt instinctively, that this guy was telling the truth about the excellent condition of the Super Glide. In fact, I was so confident that this bike was the one, that my plan was to rent a cargo van to drive to Bays' house to see, buy and take the bike home.

I told Bays, "Look, just hold off on the other guy. I'm prepared too come to you on saturday with four grand in cash and a truck to take her home." He said, we'll see. I did tell him that I'd have to see her running. He said he'd have to buy a new battery, but he'd have her running for my inspection.

We rented a cargo van from a Hertz agency on the west side of Manhattan, and found our way to the Bays home in Canarsie. As we approached his house, I heard her before I saw her.

"BRRRRRAAAACKAAaaaaa..."

The Call of The Wild.

Bays had just started the bike up as we drove down Bays' block. Hearing her voice made my palms sweat and the hairs on the nape of my neck bristle. As we drove up, she came into view.

There she was. Beautiful. A 1971 Super Glide with a Frisco mounted Sportster tank, and an OEM rear fender, that someone had grafted a diminutive ducktail on the end of. The tin was painted purple. Man, that color had to go. Black is beautiful, baby.

Bays took me for a ride (he didn't want a stranger riding his bike). This was possibly the second time ever, that I've been a passenger on a Harley. Weird feeling, man. I hate the feeling of being on the back of a bike. I like to be in control of the motorcycle, not at the mercy of another rider's actions and skills. There are too many variables with this, to reach my comfort level.

The bike ran perfectly. All four gears engaged. The motor humming, straight pipes blaring as only a shovelhead can. The bike was perfect. To make a long story short, I paid Bays the four grand in cash, loaded my bike into the truck, and we trucked on back home. Done deal, baby.

The rest is history. I would eventually name this majestic Harley 74, "Mabel."

In 1989, I picked up an issue of Iron Horse magazine. I'd gotten out of the habit of buying biker rags, because they'd become so much gibbering dreck. There was nothing really worth reading for the thinking biker. I noticed how different Iron Horse was, and began reading it religiously. Great stuff from this guy David Snow, man! There was a literary quality in his writing, and his formatting of the magazine that just set it apart. I finally found an intelligent biker magazine to read and appreciate.

I wrote to Iron Horse's editor, and asked him if he would be interested in doing an article on my bike. He agreed, and the article appeared in Iron Horse issue number 100. The title of the article was, "Genghis Rides A Harley." The editor, David Snow, knew that I was a columnist for martial arts magazines. I sent him copies of some of these articles to look over, and inquired as to whether he'd be interested in my submitting articles to Iron Horse. Snow agreed, and I sent articles in that began appearing in the magazine.

After several months of my articles appearing every month, Snow approached me with a question. Interestingly, this occurred at a movie theater in the Lower East Side where "Single White Female" was showing. Patty and I had gone to the movie, and Snow and his wife Shawn just happened to go to the same show. We ran into each other, and Snow said, "Listen, you're in the magazine every month anyway, you might as well have a monthly column. Whaddya wanna call it?" I wanted to call the column, "Going The Distance," because the title reflected what I thought a biker's relationship with his motorcycle should be.

Keep your motorcycle.

It's hard to believe that it's been twenty-two years since I approached Snow about writing for the late and great Iron Horse magazine. The very first submission I made to Iron Horse, posed this question: Who can go the distance with their motorcycle? It is my belief that a biker's honor depends on his ability to keep his motorcycle, no matter what. The classic case of a biker punking out, is when a biker sells his bike when times get tough. Hey man, dig it. When times get tough, the tough keep their motorcycles. This all goes to how a biker relates to his motorcycle, and this has been the root of what I've been trying to say in my writing about the biker subculture, for the past two decades.

The motorcycle is the basis for a biker's existence.

Do you remember the "who's a biker?" debate in Iron Horse, initiated by Snow? The answer is so stunningly simple, I'm surprised that anybody would consider the answer to be a matter of rocket science, or a complex philosophical question requiring days of introspection, intense navel-gazing and professorial insight.

It is as simple as this: Keep your motorcycle. Most of you know my history. You know that I've never been without a Harley since 1968. The point is, I'm not sittin' here counting the years and trying to impress people by setting some sort of abstract record. I'm trying to make the point that you as a biker, should not sell your motorcyle, no matter what exigent circumstances may darken your door. That's the point. Keeping one's motorcycle is a test of toughness of the biker, just as surely as enduring injuries and pain in martial arts training, is a test of toughness for the martial artist.

When I cite in my writing how I've resisted selling my Harleys in tough times over the years, but never did, I'm not offhandedly patting myself on the back, puffed up with an irrelevant sense of pride. I'm making the simple point that I've done what a biker is supposed to do, and that is to keep his bike, and ride.

All roads lead to Rome. If you look at the variety of topics I've covered in my writing about the biker subculture, you will see that everything converges in each article to an underlying and maybe sometimes subliminal message. That message is my Rome, and it is this: Keep your motorcycle, endure as a biker, love your motorcycle, because your motorcycle is the one entity that gives you life, identity and your purpose. All my articles point to this, even in this far and wide ranging memoir. Later.

FINITO