Click here for Home

GOING THE DISTANCE

"MEMOIR PART 5"

by GENGHIS

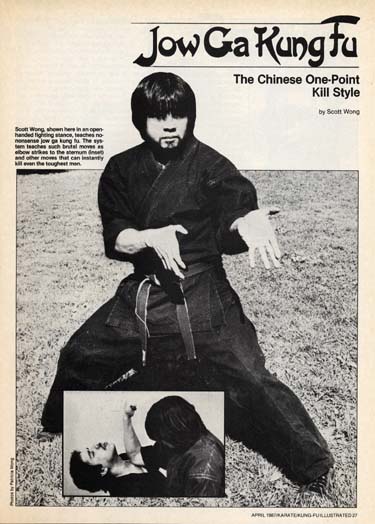

Photos by Patricia Wong

Magazine page courtesy of Rainbow Publications

BEFORE IRON HORSE:

I was a columnist in Karate-Kung Fu Illustrated magazine.

When I lived on East 3rd Street in Alphabet City (a notorious neighborhood in the East Village section of New York City, whose nickname arose from the names of the avenues in this rough and tumble, 14 block-long neighborhood filled with crime, heroin addicts and general mishcief and mayhem: These were Avenue A, Avenue B, Avenue C and Avenue D) in the late '60s, the Puerto Rican kids in the 'hood called me "Chino Hitman." This was because they suffered the stereotype-hyped misconception, that I actually knew something about the martial arts. Taken a step further, they might've assumed because of my Chinese enthnicity, that I couldn't drive. The truth is, sorry to those folks who would like to believe in asian stereotyping, but I've always been a great driver as well as bike rider. My friend Dennis Fanning, a retired NYPD sergeant, tells me that a running joke in the NYPD is that asians are sometimes busted for "DWO:" Driving While Oriental. What those kids didn't know was, I knew as little as they did with respect to combat arts technique, and this knowledge came from the same source that filled these kids' reservoirs of martial arts know-how: Watching bad kung fu flicks, and Bruce Lee movies (although his were more realistic than the run-of-the-mill Hong Kong kung fu flicks). Those movies did play a part in stimulating my interest in pursuing the study of the combat arts.

The fact that I was a biker didn't hurt the aura of the "Chino Hitman" persona, and I admit that I never discouraged my street rep as the Chinese hitman. After all, not actively dissuading people of their misperceptions isn't lying. It is merely a benign and judicious neglect of the truth, if that makes sense to you. Judicious, because nobody ever bothered me on the streets because of my ill-deserved street rep. This in itself, not ever being mugged, was an accomplishment in Alphabet City, where being mugged was a common occurrence. The Chino Hitman persona was to the general good, and gave me cred and respect from the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican street gang, a couple of whom I'd befriended from my block. One of their clubhouses was across the street from my building on 3rd Street. I taught one of 'em photography, and tried to keep him out of trouble. His street name was Chocolate'.

In 1973, my first wife Nancie, my son Mike and I moved from 3rd Street to a co-op further downtown. This neighborhood, further south in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, was a decided improvement over the crime-riddled Alphabet City neighborhood we left behind. This new apartment was on the 21st floor of a building whose haunches sat on South Street, which straddles the southeastern coastline of Manhattan island. Think of South Street as the service road of the FDR Drive (The FDR Drive, previously known as East River Drive, is a coastal highway that lines the eastern border of Manhattan island), which runs parallel to the East River. I still live in this apartment with my wife Patty. I hated the move from 3rd Street to our new place, because of the work involved. Moving has to be one of the most unpleasant experiences within the context of normal life. I vowed after that to never move again, and I've kept that promise to myself for 40 years, now. I'm a rooted type person, fer sure.

Just after we moved into our new apartment, my mother-in-law Helen Hewitt and her husband Herb visited us. During this visit, a neighbor named Helen Kollas from the one of the lower floors dropped by to welcome us to the building. Helen Kollas was fully ethnically Greek, but with incongrously blonde hair and green eyes. After Helen Kollas left, my mother-in-law Helen said to me, "Scott, you'd better watch that one. She's got something for ya." Nancie and I laughed this off, but that laughter preceded a period when Nancie and I grew apart, that led to our divorce. My mother-in-law's seemingly jocular remark, was accurately prescient. Later, after Nancie and I broke up, a laughing matter became a serious matter, when I entered a relationshp with Helen Kollas. Ironically, this relationship lasted slightly longer than my first marriage.

Within the first year that Nancie and I lived in this new apartment, our daughter Tiffanie was born, and it was shortly after her birth that our last rough marital period took place. I spoke of this before in "Memoir Part 1". Although the end to our marriage may have seemed sudden at the time, our problems were stealthily bubbling beneath the surface like warming lava at a medium simmer, in a slow-boiling volcano. What precipitated the final break up was an act of infidelity on Nancie's part. What compounded the problem, was a much earlier incident of unfaithfulness on her part, that I tried to forgive. As far as I'm concerned, infidelity is the ultimate betrayal. There can be no successful bridging of the trust gap following such betrayal. Nancie and I agreed after the breakup, that I would keep the apartment on South Street, and she would find another apartment.

In the immediate aftermath of our break up, Helen Kollas stopped by to offer sympathy and solace. This offering of succor, led to a relationship that lasted about five years (It looked like my mother-in-law was right). This relationship never felt to me like it transcended the level of a relationship that was convenient. I suspect that it may have felt the same to Helen, but there were times during those years when she wondered aloud, whether a Greek wedding would ever take place for us. It was all too convenient for the both us, to really commit. We lived two floors apart, and when we each got what we wanted, we retreated to our own corners of solitude every night. After about a year after my relationship with Helen began, Nancie wanted to come back to me, but I rebuffed her. I told Nancie that I couldn't return, not only to the uncertainty about trust, but the almost daily arguing and fighting that Nancie seemed to need and thive on. That closed the chapter on our marriage, and we then quickly and painlessly divorced.

In 1976, I began taking a long look at possibly training in the martial arts. This, at a relatively old age of 29. Most serious students of the arts begin at a much earlier age. How I ended up Richard Chin's Asian Martial Arts Studio in the Soho section of lower Manhattan, was described in some detail in "Memoir Part 1". I thrusted myself heavily into my training at this school, whose no-nonsense and hard-hitting attitude was the polar opposite of "tag-playing," black-belts-for-sale, shopping mall karate studios. In this dojo, one earned his rank by demonstrating competent technique and mental and physical toughness. Being tough was emphasized as much as technical proficiency. I soon began spending five nights a week training at this dojo, and it took me four years to earn my black belt there.

I also became a disciple of my teacher's. The discipleship system is difficult to describe to the lay public. To illustrate this point, when I told a friend of mine named Fred Eickelberg about my discipleship in our dojo, Fred commented (only half-jokingly), "Why Scott, that sounds like a cult to me." With discipleship in a dojo, one is part of the inner circle, which not only gives disciples the extra attention of the teacher, but also bestows the responsibility of running the school and making sure that the art is propagated by the disciple. Think of it as making full patch after prospecting for a motorcycle club. Often, making black belt rank in a traditional school coincides with becoming a disciple, but not always.

A case in point in our dojo, was a karate black belt named Graham. It was a truism repeated in our school, that a student is not taken seriously until he makes black belt. In making black belt, Graham demonstrated that he reached the point which is considered merely the starting point of serious study in the traditional combat arts. However, Graham never made disciple in our school because he had perceived deficiencies not related to fighting technique. In commercial schools, making black belt rank is seen as the be-all and end-all goal. In traditional schools, making black belt is only the beginning of long-term training.

Discipleship programs don't even exist in commercial schools, where the bottom line of the almighty dollar dictates that belt ranks are given out after a period of attending classes has passed, without true regard to how good and tough, the student is. This results in many schools, in meaningless rank. The perfect example of meaningless rank is the ten year old black belt, which is a common phenomenon in commercial schools. Soccer moms who drop their kids off at the shopping mall dojo are paying good money for classes, and they expect their kids to get rank! Or else they'll find a dojo that will provide what they want. This consumeristic expectation is fine when buying a product, but does not apply to traditional combat arts. A million dollars can be spent over a 20 year period in a traditional school, and if yer not good enough and tough enough to warrant that black belt rank, you're not going to get it. This concept of child-age black belts cannot be taken seriously, for obvious reasons. Taking a 10 year old black belt seriously, is like taking a 10 year old biker seriously. Do ya really think that a 10 year old's gonna climb on his Harley 74 and take off? Get real, man.

Discipleship programs are generally hidden from the general students of a dojo. Discipleship as a tradition, isn't just Chinese. The Japanese have a similar system in which a disciple of a sensei (teacher) is known as uchi-deshi, meaning "inside student." Being on the inside implies grave duty as well as privilege. The duty part is well understood: The disciple has to be able to teach in the school, and to take over and run the school if necessary. The privliege, is to be taken seriously by one's teacher, and ensures that the teacher will reciprocate in his duty to provide truthful and intense knoweldge and training, to ensure that the disciple develops fully as a combat artist and a teacher of the martial arts style of that school. Think of discipleship as a true apprenticeship, versus merely paying for lessons.

Richard Chin's Asian Martial Arts Studio was located at 162 Wooster Street in the Soho ("South of Houston Street") neighborhood, which is directly adjacent to Greenwich Village in Manhattan. This is an artsy area dominated by art galleries and artists' lofts. The dojo was cavernous on the inside, which belied it's smaller appearance from the street. From the street, the dojo presented the face of a somewhat wide (approximately forty feet wide) storefront, with the name of the studio in front, with a painting of a yin/yang symbol on the window. In fact, the dojo was much longer than its width, as one found out when inside. The whole window was covered with this mural, so it was not possible to see inside. When one entered the dojo, one was herded down a narrow walkway on the left, with Quonset huts standing on the right. This walkway and the Quonset huts extended inward about thirty feet, ending at the floor of the dojo. The actual training floor was huge. It was 40 feet by 60 feet. Between the "floor" and the Quonset huts, was a small observation area with chairs, and an altar against the wall on the right. The altar held a bowl with sticks of burning incense. The incense sticks were only for the disciples. Only disciples were allowed to light incense at the altar.

This is the world of deep tradition, represented by the etiquette followed, that I entered in 1976 at the age of 29. When I enrolled at the Asian Martial Arts Studio, there were many general students, but only three disciples. These were Laura Gaines, Jeff Pascal and a guy named Greg. Greg moved out of state shortly after I joined, so I didn't get to know him very well. Laura and Jeff had black belt rank, while Greg was a karate brown belt. Laura Gaines had her rank in the Okinawan karate style of Kuen Do Ryu, one of the two styles that Richard Chin taught. Laura in fact, held the lease to the dojo space. Laura was an artist by trade, and this allowed her to be able to lease space in this art-oriented neighborhood. Laura was also Richard Chin's girlfriend. Laura lived at the dojo, using the Quonset huts as her living space. Richard Chin's other disciple, Jeff, was an affable sports goods salesman, who had extraordinary athletic talent and a strong background in judo and grappling.

I knew that I wanted to become a disciple at the Asian Martial Arts Studio, because I became fully immersed in my training there. I wanted to teach someday. It was an area of intense interest in my life. It took me three years of steady training before I was accepted as a disciple. By that time, another student who joined the dojo shortly after I did named Mike Willner, had made black belt rank at an accelerated pace, and was a first level disciple. There were two levels of discipleship, the second level being the highest. This was separate from technical belt rank. I followed the tradition of taking all of the disciples to dinner (all of our discipleship dinners took place in Chinatown). This represented my official application for discipleship, and the signal that I was accepted into the inner circle of apprentices of Richard Chin's. This was not so different really, from the ceremonial trappings of a prospect making full patch in a motorcycle club. The feeling and general sentiment, are the same.

By 1980, four years after my enrolling in the Asian Martial Arts Studio, I made entry-level black belt rank in Jow Ga, the kung fu style that Richard Chin taught. By this time, because of the unfiltered way that we trained, I had sustained many injuries. Unlike in commercial schools, we practiced full-contact sparring with minimal protective equipment. This equipment consisted of a groin cup and a mouthpiece. Full-contact hitting was not only encouraged, but mandatory. Any students in the Asian Martial Arts Studio who felt compelled to hold back on hitting sparring opponents with full force, were ostracized from the school for lacking the killer instinct that was deemed a basic requirement for an effective martial artist. This was heavily stressed by Richard Chin, as it was by me when I began teaching. A martial artist with good technical proficiency, but lacked the will to try to inflict maximum damage, is but an empty shell, unable to fulfill his potential. Among the injuries I had over the years from my training, were a broken jaw, broken ribs, broken foot, broken wrist and elbow and knee injuries. Included in there were a couple of concussions. This was all par for the course in our dojo, and accepted as the norm as simply an unavoidable part of real training.

By the time I became a first-level disciple in the dojo, my relationship with Helen Kollas was winding down, as a function of attrition and lack of commitment. Although we spent a lot of companionable time together during our relationship, it wasn't deep enough in commitment to be sustainable. Around 1982, Laura Gaines lost the lease for the space on Wooster Street where the dojo had sat for years. By this time, there were five of us under Richard Chin, who held black belt rank. Besides me, there was Jeff Pascale, Laura Gaines, Mike Willner and Graham (I forget his last name). There was a famous anecdote about Graham, and it went something like this: When Graham was a beginning white belt student, a mugger accosted him in an alley in the Lower East Side, and hit Graham several times in the face. Graham just stood there, not reacting in any normal way, or in any way at all. Graham just stood there glaring at the mugger with a cold, murderous look in his eye. He was like an emotionless android gettin' ready to counterattack. This true story ended with the mugger becoming so freaked-out, that he took off running. Graham was a tough son of a bitch. Graham though, was the only non-disciple black belt in out school. He was tough, but there was just something lacking in him that prevented his being accepted as an uchi-deshi.

In 1981, Laura Gaines was unable too renew her lease at 162 Wooster Street, and we lost our dojo space in Soho. The Asian Martial Arts Studio effectively split into two separate branches, run by Mike Willner and myself respectively. Mike established a dojo in uptown Manhattan, while I established a dojo at the Third Street Music School in downtown Manhattan. Richard Chin's school became in reality, the Asian Martial Arts Studio Downtown, and the Asian Martial Arts Studio Uptown. The Third Street Music School was actually on 11th Street between Second Avenue and Third Avenue in Manhattan, and was an historically significant New York center for the arts founded in 1894. It is the oldest school for the arts in America. We were able to procure a dance floor space there as our dojo, because Jeff Pascale's girfriend, Ann O'Neill who was one of our karate students, worked at the Third Street Music School. By this time, I was promoted to second-level disciple. I was at this point, the only second-level disciple. This established me as the highest ranked disciple in Richard Chin's school. At this 11th Street dojo, I taught both styles, Jow Ga and Kuen Do Ryu. It was at this dojo, where I would meet my future wife, Patricia Anne Cicchinelli. More to come. Later.

FINITO